Innovative Minds © 2014. All Rights Reserved. www.inminds.co.uk | ||||

|

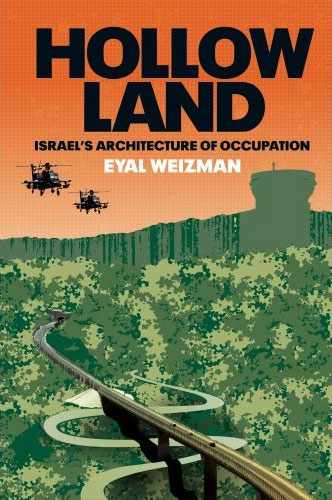

Comment: Architect Eyal Weizman looks at the occupation purely from the perspective of architecture and building planning. His research is truly insightful. He looks at how the shape of a israeli settlement on the West Bank has evolved over the decades to reveal its true function. He explores the path the Israeli tanks and bulldozers took in their attacks on Jenin and Nabulas to reveals their hidden agenda. He sees the changing path the apartheid wall takes through Palestinian land as an unraveling power play between different israeli factions - all wishing to expropriate Palestinian land but in different ways. All fascinating stuff! Watch the 87min lecture he gives at the Baker Institute - its a good appetiser for his works. Interesting with regards to a two state solution he concludes "architecturally, planning-wise, it's entirely unfeasible". We agree, a Palestine from the sea to the river, free from zionist occupation, where Muslims, Jews and Christians can all live together in peace is the solution. Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of OccupationEyal Weizman New Book: SynopsisThis is a brilliantly original examination of Israel's terrifying reconceptualization of geopolitics in the Occupied Territories and beyond. "Hollow Land" is a groundbreaking exploration of the political space created by Israel's colonial occupation. In this journey from the deep subterranean spaces of the West Bank and Gaza to their militarized airspace, Weizman unravels Israel's mechanisms of control and its transformation of the Occupied Territories into a theoretically constructed artifice, in which natural features function as the weapons and ammunition with which the conflict is waged. Weizman traces the development of these ideas, from the influence of archaeology on urban planning, Ariel Sharon's reconceptualization of military defense during the 1973 war, through the planning and architecture of the settlements, to contemporary Israeli discourse and practice of urban warfare. In exploring Israel's methods to transform the landscape itself into a tool of total domination and control, "Hollow Land" lays bare the political system at the heart of this complex and terrifying project of late-modern colonial occupation.  Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation by Eyal Weizman AuthorEyal Weizman is Director of the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths College, University of London, and has worked with a variety of NGOs and human right groups in Israel-Palestine. He is an editor-at-large of Cabinet magazine, and received the James Stirling Memorial Lecture Prize for 2006-7. Book Details* Hardcover: 288 pages * Publisher: Verso (4 Jun 2007) * Language English * ISBN-10: 1844671259 * ISBN-13: 978-1844671250 * Product Dimensions: 23.6 x 16.3 x 3.6 cm Related Items

Lines in the sandEsther Addley, The Guardian Israeli architect Eyal Weizman won a competition to represent his country at an international conference. But the invitation was abruptly cancelled when it was discovered that his work criticised Israel's illegal settlements in the West Bank. He talks to Esther Addley about the politically loaded nature of planning in the region

It is extraordinarily detailed, almost unfathomably so, and that is partly Weizman's point. If you thought the Israeli/Palestinian conflict was fiendishly complicated, he is saying, you are wrong: it is much more complex than that. And intentionally so. "Complexity was always a propaganda technique of Israel. Whenever you speak to an Israeli politician and you say, 'Well, why don't you retreat', they say, 'Oh, it's far too complex'. So the territorial aspect of the conflict has become very much the domain of experts, and that was what Israel wanted. If you are not an expert, everything you argue they can tell you, 'Oh, it's unfeasible.' Whereas we want people to understand, we want to make it as clear as possible." Unashamedly of the Israeli left, the 31-year-old, who also lectures at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London, says he set out to critique the policy of illegal settlements not primarily with moral or legalistic arguments, but having reached his conclusions from architectural examination. "If you are an architect and you understand that the main manifestation of this conflict is through the landscape and the built environment, it is almost your responsibility to act vis a vis that. It would be bizarre now for me to engage just within a normal architectural practice in Israel, building houses and so on." That reluctance, however, is where the trouble began. Earlier this year, along with his partner in his Tel Aviv practice, Rafi Segal, Weizman won a national competition to curate the Israeli stand at the World Congress of Architecture, a biannual event taking place in Berlin this week. Their exhibition, The Politics of Israeli Architecture, undertook the first detailed examination of the spatial form of Israeli settlements in the West Bank, examining how their physical layout is informed by the politics behind them. The catalogue to the exhibition is illustrated with scores of unsettling, but quite beautiful, photographs of settlements taken by the architects themselves while overflying the whole region. It also contains detailed blueprints for the layout of settlements, documents explicitly called "masterplans" by their creators and supposedly in the public domain, but which the pair had to threaten going to the Israeli courts in order to be able to see.  Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture, by Eyal Weizman, Rafi Segal, David Tartakover (ISBN-10: 1859845495, ISBN-13: 978-1859845493) No one at the Congress will see them, however. Earlier this month, Weizman and Segal's stand at the WCA was abruptly cancelled by the Israeli Association of United Architects. Uri Zerubavel, the association's head, told the Israeli newspaper Ha'aretz last week, "The association thinks that the ideas in the catalogue are not architecture. Heaven help us if this is what Israel has to show. As though only settlements... were built here... My natural instincts tell me to destroy the catalogues, but I won't do that. I won't burn books." The association has insisted, however, that Weizman and Segal stop distributing the catalogues immediately. (They have refused and it will be published by Babel in Tel Aviv next month.) The architects insist that the IAUA knew the content of the exhibition, but concede that the material it contains is potentially controversial. "We realised that we could understand the processes of human rights violations not only in quantified space that has been taken, in statistical terms, but that it is the very form and layout of settlements on the urban level, and their positioning within the terrain on a territorial level, that is in breach of basic human rights." But how can a small town full of civilians infringe people's human rights? "If you look at the layout of settlements, they are always built on hilltops. People know that, but they may not realise that they also are built in rings, over the summit, in a way that generates territorial surveillance in all directions. I began to understand that these are urban-scale optical devices, and every design move in them is calculated to enhance vision." Only by looking at the original architectural plans, he argues, would one register something so simple as the fact that each house is built with its bedrooms innermost, its living quarters facing the vista. "The planners always speak about the view as pastoral and biblical, almost in a romantic sense. They speak about the terraces and olive groves and stone houses, which are obviously created for them by the Palestinians. The Palestinians are almost like the stage workers who create a set, but they then have to disappear when the lights come on." But it is not only the Palestinians' rights who are infringed, he argues. "The army also uses the eyes of the civilian settlers, almost hijacks them, to generate territorial surveillance. There is almost an illegal use of civilians to generate supervision of another part of the civilian population." The more Weizman tries to elucidate his understanding of the way the space of the occupied territories has been partitioned during the conflict, the more difficult he is to follow. In a series of articles entitled The Politics of Verticality, the architect has argued that the division of territory along vertical as well as horizontal planes - the only way the two communities can put into practice their demands for entirely separate sovereignty over the same space - makes the West Bank and Gaza, crucially, a disputed three-dimensional volume rather than two-dimensional area. Even where the Palestinian Authority was nominally given sovereignty of the surface of a section of the territories under the Oslo Accords, he points out, Israel retained sovereignty of the airspace and the subterrain. "So they had to come up with bizarre and insane projects like tunnels and bridges, so an Israeli road would go under a town that the Palestinians have sovereignty over, meaning that the international border is in section. Architecturally, planning-wise, it's entirely unfeasible, and it makes no sense. " But such a definition, surely, makes all planner maps obsolete, even his own? Weizman agrees, describing the current situation as "Escher-like, a territorial hologram". There are six dimensions at play in the West Bank, he says, three for the Israeli space and three for the Palestinian. "It creates a totally dystopian and weird space. It becomes so intense, it just collapses." Weizman's conclusion gainsays most diplomatic thinking: he argues that the dream of two discrete states carved side by side is now unworkable. "It makes no sense to have an iron curtain or a concrete curtain between Israel and Palestine and have two nation-states. Even if you build tunnels and bridges, and partition the airways and the subterrain, what do you do with Jerusalem? Somebody calculated that you need 64km of wall in Jerusalem alone to partition Israelis from Palestinians, and 40 tunnels and bridges to join the different areas. This is an ecological and planning nightmare, and it is a nightmare for the economy of Jerusalem. It is nonsense. It is the ideas of politicians who don't understand territory or architecture or planning." So what possible resolution can there be? Weizman's solution, fittingly, is a planners' one. New maps need to be drawn, he argues, which illustrate the two parties' geographical, ecological and infrastructure interdependence, emphasising the importance of such factors over political outlines. His hope is that this would eventually create a "functional integration" which would, in time, come to supersede political myth-making. "Obviously it sounds like a totally wacko idea now, but I am a real believer in this kind of bureaucracy. There needs to be a process set in motion for an incremental functional union. He knows that such a plan requires the complete abandonment of the Zionist project on the Israeli side, and of Palestinian national aspirations? It is far away but I think it's not that weird." "People in Israel don't really understand the political use of space [in the West Bank], they don't really understand where things are." That was one of the reasons behind his determination to create a more accurate map, he says, and to present the full detail of the settlement layouts, before he was silenced. "They want to say that architecture is nothing to do with politics, but architects and planners have always been the executive arms of the Israeli state, erasing the old cartography and trying to create their own on top of it."

Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk/israel/comment/0,10551,762659,00.html Israeli government censors architectural exhibitionTim Tower, World Socialist Web Site In an effort to stifle and conceal mounting opposition within Israel to the war against the Palestinians, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs has initiated a witch-hunt against two prize-winning architects and prevented their work from being displayed at the World Congress of Architecture in Berlin, Germany and at the Venice Biennale in Italy.

A most noticeable feature of the map is the disparity between the settlements, municipal boundaries and their actual built-up areas...

Eyal Weizman The move came when the cultural representative of Shimon Peres, foreign minister in the Likud-Labor coalition government, inspected display boards and a catalog titled, âA Civilian Occupation, the Politics of Israeli Architecture.â The work, compiled and edited by architects Eyal Weizman and Rafi Segal, had won a national competition to represent Israel at the World Congress of the Union Internationale des Architectes (UIA), which convened in July in Berlin. The exhibition examines Jewish settlements built over the last century. Articles by geographer Oren Yftachel, architects Sharon Rotbard and Zvi Eftrat and journalists Gideon Levy and Meron Benvenisti appear in the catalog, as does an interview with architect Tommy Leitsdorf, who planned the towns of Maâale Adumim and Emmanuel. Photographs by Milutin Labudovic, Miki Kratzman, Pavel Wohlberg and others also appear in the catalog, as do maps, plans and diagrams of the settlements. A map, prepared jointly by Eyal Weizman and Bâtselem, the Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, was a central feature of the exhibition scheduled for Berlin, as well as figuring prominently in the Israeli Pavilion, which is currently on view at the Venice Biennale. In both cases, the map became a target for censorship. At Berlin, the entire exhibition was suppressed. In Venice, the exhibition went forward, but the map was altered to obscure its political content. The banned catalog explains the controversial message, which the map conveys, stating, âThis map is an up to date description of the Israeli settlement project in the West Bank. It marks the location, size and form of Israeli settlements, the scope of their potential expansion, and the total amount of State Land at their disposal. The built-up areas of the settlements occupy only 1.7% of the land in the West Bank, but their municipal boundaries and regional councils control a total of 41.9% of the land.â The map provides graphic information about both Jewish and Palestinian habitation and shows âhow the settling of 380,000 Israelis in the West Bank achieved the complete fragmentation of the territory.â The text describes the care taken by its authors and the difficulties they encountered in compiling information. âThe map is a synthesis of a large number of maps, master plans, regional plans, and other data,â it states, and âis the outcome of an eleven-month process of collection, analysis and charting. The 150 original settlement master plans proved difficult to get hold of. Obtaining them usually necessitated traveling to individual settlements, sometimes even legal action against deliberate delays.â âA most noticeable feature of the map,â write Segal and Weizman, âis the disparity between the settlements, municipal boundaries and their actual built-up areas. Since settlements can still grow within their existing boundaries, this map, besides describing a present set of affairs, in fact, outlines a possible future.â Alarmed by its critique of Israeli settlements on the West Bank, Peresâs agent immediately phoned the President of the Israel Association of United Architects (IAUA), the Israel Ministry of Cultural Affairs and the National Lottery to force the displayâs withdrawal. Describing their depiction of the West Bank, Eyal Weizman told the WSWS by telephone from Tel Aviv, âAny Israeli who sees it is shocked. What the map shows is the size and distribution of the Jewish settlements and the areas, which are designated for future expansion. It reveals what is not understood.â Weizman went on to explain the difficulty for Israelis in obtaining a clear understanding of what is happening. âThere is always camouflage, a type of smokescreen, when you ask about the settlements,â he said. âComplexity has become a technique. Explanations are very Talmudic and complexâa lot of verbal rhetoric. It is all very alienating. If you are not an expert, you cannot say anything. The same drive for complexity is what is behind the action of the Foreign Ministry.â With co-editor Rafi Segal, an architect who has won both the Young Artist Prize and the Young Architect Prize of the Israel Association of United Architects (IAUA), Weizman has undertaken a historical review of the architecture and planning in the Occupied Territories. âOur idea was to give it form, so people understand it,â he told us. âWe have to be precise and clear. There are human rights issues in these structures. They are illegal. They have to be dismantled.â IAUA President Uri Zerubavel responded to the intervention by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs by denouncing the architects, withdrawing support for the exhibition and threatening further legal and professional reprisals. In his letter, terminating the exhibit, Zerubavel wrote, âWe prohibit any connection between the exhibition, the paraphernalia of the exhibition and the catalog and the Israel Association of United Architects.â The IAUA chief concluded his letter by threatening to deregister the authors. âThe damage caused by you to the association is great, and we are assessing it,â he wrote. âAny breach of our demands in this matter, any use of the associationâs name or of its members and heads in connection to the exhibition paraphernalia will cause us to take steps against you, and this is beyond the damage that has already been caused to our image in Israel and the world.â Rafi Segal explained that the IAUA had been well informed about the content of the exhibition in advance. The theme and many of the contributions to the catalog had been presented as part of the competition held last year; and subsequently regular meetings were held. âWe had a monthly meeting for seven months with this committee,â he said. âThey knew the contents. They saw the photos. They knew who was going to write.â Despite the fact that the selection process had been conducted publicly, the IAUA chief reported to the press that the association had been deceived. âThe association is apolitical,â he said, terming the catalog âan anti-Israeli, one-sided presentation, with totalitarian graphics, pictures of soldiers and tanks, every page about Israeli occupation. We could not accept it.â He did admit, however, that the executive committee of the association was split 15 to 5 over the decision to censor it. If the IAUA is not political, its president must explain why the leading committee convened for the sole purpose of executing a political attack on two of its members. In response to the attack, other members of the IAUA mounted an exhibition in support of Weizman and Segal, showing all the competition entries alongside a single copy of the banned catalog. The association executive committee demanded that the exhibitors include a separate wall for the competition photographs and writings submitted by Segal and Weizman last year. The implication was that the chiefs had been willfully deceived. But when the exhibitors complied with their request, the photographs and writings from the competition and from the catalogue proved to be substantially the same. No deception had occurred. The only reasonable conclusion to be drawn is that a change in attitude at the IAUA was brought about by the intervention of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Source: http://www.wsws.org/articles/2002/sep2002/isra-s16.shtml The Wall and the Eye: An Interview with Eyal WeizmanSina Najafi and Jeffrey Kastner, One of history's most fiercely contested landscapes, the 2,270 square miles of territory known as the West Bank was under the control of Jordan when it was occupied by Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War. Over the last 35 years, the area has become home to some 200,000 Israelis (400,000 including occupied East Jerusalem) who populate numerous, new, purpose-built settlements perched on its hilltops, overlooking long-established Palestinian lowland communities. This ongoing state-sponsored policy of expansion onto the high ground has been paralleled by the development, within the architectural and urban planning professions, of extremely particularized strategies for building on heights. Many of these draw on historical precedents; all are designed to provide basic municipal amenities within a context of highly refined, surveillance-based security. A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture, a catalogue and exhibition originally created by Israeli architects Rafi Segal and Eyal Weizman as their country's official entry to the 2002 World Congress of Architecture in Berlin, is a ground-breaking examination of the character of building, planning, and community in the West Bank. Abruptly cancelled last summer on the eve of the Congress by its commissioning organization, the Israel Association of United Architects, the project has stirred strong opinions in Israel. Although it was dismissed by the association's president as "one-sided political propaganda," A Civilian Occupation was praised as a "a rare work in its power and importance for the community of architects and town planners in Israel" by the daily newspaper Ha'aretz. Since the cancellation, Segal and Weizman have found other forums for the work they produced: the catalog is being reprinted by Babel Press in Tel Aviv and a version of the exhibition will be be mounted at the Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York, at the end of January and in the exhibition "Territories" at Kunst-Werke, Berlin, in May 2003. In the following interview, Weizman, a partner in Tel Aviv-based Rafi Segal/Eyal Weizman Architects, discusses both the natural and built environment of the West Bank â from the social, political, and religious history of the area to issues of photography and mapping to concepts of strategic building forms and settlement growth patterns. He also asks pointed ethical questions about Israeli architectural and planning practice and considerations of human rights, which he says are central to the research he and Segal continue to conduct. Weizman spoke by phone to Jeffrey Kastner and Sina Najafi from Haifa, Israel, in October 2002.  Photographs: Milutin Labudovic for Shalom Achshav, 2002 Your catalogue cites a 1984 publication by the Israeli Ministry of Housing that sets guidelines for the construction of new settlements in the mountain regions of the West Bank. It's very concrete: it proposes an inner ring and an outer ring of houses, discusses the idea of offering the maximal amount of views to the maximum number of settlers, which obviously also allows a maximum amount of surveillance of the Palestinian population beneath, and so on. This is interesting in light of the interview in your catalogue with the planner and architect Thomas Leitersdorf about towns he has built in the West Bank, where you get a sense that sometimes the government offers no guideline other than "We need a town built here," and the architect is completely left on his own to do whatever he wants. So we have this severe set of guidelines versus no guidelines at all, apparently at the same time. When Leitersdorf built Ma'ale Edumim in 1977-78 he was in effect setting the guidelines. Ma'ale Edumim was essential in creating a benchmark standard for building settlements. In general, Israeli architects and planners had little experience of building in mountainous regions. Before the occupation, the Israeli population was located mainly in the valleys, except in Haifa, which is a mountain city, and in Jerusalem. The typical new Israeli settlements were the kibbutz and the moshav, cooperative agricultural and pioneering settlements built mainly on the fertile plains. It is only after the occupation, and following the political changes in 1977, that the mountain enters the public imagination â people write songs about the mountain, talk about it, lecture on it, research it. Architects were starting to think about the mountain too, but they had little experience of building there. So this publication by the Ministry of Housing was incredibly important because it collected different precedents and for the first time set guidelines for how to build in the mountains. The "mountain" is important in understanding the ideological transition in Israel after 1977, when a messianic religious discourse entered the political debate with the right wing coming to power. Along with it came a decreasing emphasis on agricultural pioneering and its replacement with a new typology of the religious suburb, located on mountaintops and without agricultural space to cultivate.  What are the historical sources for this relationship to the mountain? If you look at the geography in Biblical times, the Israelite settlements were primarily in the mountain regions of Judea, Samaria, and the Galilee, whereas the plains were inhabited by the Philistines. So there is a geographical reversal, a paradox: when the Zionists came back to their "promised land," they initially settled in the places where Jewish history didn't happen within the land of Israel. The return to the mountain is a return to those sacred places, to the bedrock of Jewish identity. At this point, the mountain appears in many aspects of culture as a symbol and as an unfamiliar reality, and architecture is part of it. The government wanted to resettle the mountain and architects needed to learn how to build there, so the Ministry of Housing came up with guidelines that promoted the use of topography for the establishment of observation points. These were new urban typologies that maximized the potential of the mountain and made use of the precise morphology of the topography. Basically, if you look at the master plans of the settlements, the roads retrace the topographical lines that we charted on maps, so that each settlement takes the exact form of the mountain summit and is built around it as a ring that overlooks all directions. It's most clear in Ma'ale Edumim, where there is not just one peak but many peaks and ridges. There you see the direct translation of topographical cartography into urban form. Since mountaintops are not suited to agriculture, presumably many of the settlers are commuting. Yes. Essentially, the settlements are built there because the mountains are not suited to agriculture. It is because Palestinians could not cultivate these hilltops, where the good alluvial soil has eroded, that they could be seized by Israel and declared state land. It's a complete reversal of the logic of cultivation. Obviously the settlers have to either rely on the main citiesâ the metropolitan centers like Tel Aviv and Jerusalemâ or on industrial zones near the settlements, again on hilltops. Are those industrial centers subsidized? They are subsidized in the sense that you pay much lower income tax and council tax. You describe an important evolution toward a kind of messianic political ideology. What was going on in 1977 that specifically catalyzed this shift? The crisis point in Israeli history was 1973 and the Yom Kippur War. This was a time when the Israelis were fearing total defeat and old fears resurface. Until then, Labor Zionism was trying to reverse the traditional image of the Jew â not as a victim, but as a strong, self-sustainable new man. This exemplified itself even in the way the Holocaust was portrayed and sometimes even glorified as an act of national resistance. The national day of Holocaust remembrance, for instance, is called the Day of the Holocaust and Heroism. In 1973, Zionism experienced "the return of the repressed," with a renewed sense of doom, as the Egyptian and Syrian armies seemed to be driving toward the main urban centers, with only the incredible maneuvers of Ariel Sharon in the Sinai stopping them. But immediately after the war, with Golda Meir's government in ruins, you see the religious elements in Zionism taking control. One of the first settlements, Sebastia, was created by Gush Emunim, which is a kind of religious organization that has always pulled the government by the nose to build settlements, as if to uplift the gloom of the Yom Kippur War. It took four more years for the Labor government, which had controlled the country from its creation, to be replaced by the right-wing Likud government of Menachem Begin. And the whole settlement policy changedâ they discovered the mountain, sacredness, and archaeology again. By this point presumably the left's political clout had been much diminished. Were the settlements presented as a fait accompli? Was there a great deal of internal debate in Israel about this program of settlement building? It was always very controversial from its inception. But was it presented as a security issue or was it presented as an ideological, religious issue? Or are the two things so tied up together that you cannot pull them apart? You have all the reasons at play together; sometimes some are stronger, sometimes others. In the first 10 years after the occupation, 1967 to 1977, we had a Labor government. What they did mainly was to settle the Jordan Valley with kibbutzes and moshavs â this is what they knew, frontier settlements on the plains. Between 1973 and 1977, it was Shimon Peres who was supporting Gush Emunim. Shimon Peres was squabbling with Yitzhak Rabin for the hegemony of the Labor Party and he aligned himself with the right-wing policy of establishing settlements just in order to embarrass Rabin. So Peres was actually the first person to promote settlements even before the beginning of "the mountain ideology," before the reversal of power. As for security, up until 1979 the legal tools that the government used in order to seize land and build settlements were based on the 4th Geneva Convention, to which Israel is a signatory. The convention states that you are not allowed to build permanent settlements on occupied land, but you are allowed to build temporary interventions for security reasons. What the government was claiming was that the settlements were temporary paramilitary posts. This issue was debated twice in the High Court of Justice (HCJ). There were petitions by Arab landowners against the confiscation of their land and the building of settlements. The first one was the case over the Beit-El settlement, which produced an incredible protocol, with the HCJ judges debating urban form in terms of military-strategic potential and speaking in terms of vision and observation. The HCJ in that instance allowed the construction of these settlements, with the Israeli High Court Justice Vitkon at one point declaring that, "With respect to pure military considerations, there is no doubt that the presence of settlementsâeven if âcivilian' âof the occupying power in the occupying territory substantially contributes to the security in that area and facilitates the execution of the duties of the military. One does not have to be an expert in military and security affairs to understand that terrorist elements operate more easily in an area populated only by an indifferent population or one that supports the enemy, as opposed to an area in which there are persons who are likely to observe them and inform the authorities about any suspicious movement. Among them no refuge, assistance, or equipment will be provided to terrorists. The matter is simple, and details are unnecessary." Here the court is clearly establishing the fact that civilians and residential settlements could have a security function that is normally attributed to the police and the army. The next case in 1979 was that of Elon Moreh, where the settlers practically shot themselves in the foot by claiming they were not there for security reasons but because it was their right and this was their God-given territory. This meant that the court could no longer authorize the settlement as a temporary military intervention. They were testing this new theoretical definition of what a settlement could be, which was not related necessarily to this temporary security-based issue, but was related to some kind of divine right? Yes, the settlers felt that as long as the settlement project was judged only on strategic issues they were going to lose their credibility as an ideological-religious movement. And if other security arrangements were found, they could always be evicted. They chose a strategy but ultimately lost the case and the settlement was destroyed.  But did that lay the foundation for future claims? The government had to opt for another legal tool because they could not build settlements and argue that they were temporary strategic military outposts. They said, OK, we can rely on Jordanian law and start a project of land registry. The West Bank had not had a land registry since Ottoman times, and if you look at Ottoman land laws, you did not have real land ownership. You would just pay tax for what you cultivated. Nobody wanted to own anything beyond what he was growing on, because that is what you paid tax on. If someone fenced off a hilltop, he didn't register it because that would just mean more taxes. So basically Israel was collecting Ottoman tax documents to establish ownership and map out the extent of cultivated lands. Whatever land could be proven to be under continuous cultivation remained in private Palestinian ownership, and the rest was declared state land according to Jordanian law, which was based on Ottoman law. But legally, didn't the Israeli government have to say that the West Bank is actually their land in order to then impose a set of rules on it, no matter where they borrowed those rules from? What they were saying was that these patches of land here and there, mainly the hilltops because the hilltops were not being cultivated, were State of Israel land. They were state land because they were not under any private ownership, and Israel was the ruler of the area. There were complaints at the UN that Israel could not use state land in the way they wanted to because it was still under temporary possession of an occupying power. But Israel claimed that the West Bank was not actually "occupied land," because the UN never recognized Jordanian sovereignty over the West Bank. It was a very complex, self-contradictory and elliptical way of arguing. On the one hand, Israel accepted and relied on the Jordanian rules. On the other, it said something that is in fact true, that the West Bank was occupied by Jordan after 1948 but that the UN had never recognized its sovereignty there. You write about how after 1967 this contested land in the West Bank became one of the most photographed terrains in the world, where 3-D stereoscopic images were constructed using special double-lens aerial cameras. Are the new aerial photographs you've included in the catalogue similar to the ones the Israeli government took after 1967? Not at all. These are photographs taken by Milutin Labudovic for an organization called Peace Now in order to monitor settlement growth. They are taken at low altitudes â we were allowed to fly at 6,000 feet over sea level. The stereoscopic images were essentially 3-D reliefs of the terrain taken at a much higher altitude in order to build topographical maps. Right after the occupation, the government needed to create a map very quickly, and it was difficult to physically get to all the places, so they used this stereoscopic technique in order to recreate the structure of the mountain. Before the occupation, there were no good topographical maps of the area â there were some done by German and American evangelists who were mapping the Holy Land and some general ones done by the British mandatory power, but they were absolutely not good enough to plan and construct with. What interested Rafi Segal and me about the stereoscopic technology was that a methodology of design so clearly relied on a technical apparatus â the stereoscopic images became the primary tool with which topographical lines were charted on maps and then provided the slate for the design work itself. The desire to map the West Bank immediately after the occupation showed clearly that you don't just map things â mapping is an act of proprietorship and the whole settlement project is built upon those topographical lines, which were drafted on those photographs. It's as if those lines set the blueprints of the settlements. Was it difficult to obtain permission to take your aerial photographs? It is very difficult now after operation Defensive Shield, but previously the Ministry of Defense was allowing us very narrow slots, over the air space the Israeli air force was using and underneath the national routes. Your aerial images show a number of striking things about the details of the landscape, which nevertheless need to be "read" with guidance. One was the politics of pine trees versus olive trees. The Ottoman rules were that the state could acquire any land that had not been cultivated for a certain amount of time. So now the Palestinians are rushing to plant olive trees and the Israelis are planting pine trees, which grow a lot faster. That's true, but it's not only that they grow faster. Another reason for planting pine trees is to make a difference from the olive tree as a separate national symbol. A third reason is that pines have an acidic drop on the ground. There are no bushes under pine trees, so grazing and shepherding is very difficult in these areas that have been planted with pine. Even if you cut the pine trees, the subsequent acidity of the land is such that it does not allow agricultural cultivation. Right now we are working on an enlargement of one particular image â in a similar fashion to the kind of work that intelligence analysts do during wartime. They can see things that the untrained eye cannot. We try to reveal the hidden narratives engraved on the landscape. I think that's important because one of the things our editorial group discussed when we were looking at the aerial photos is the degree to which they aestheticize the information. It sounds like the project you are working on now is one of particularization â putting specific information along with the images. That seems to make a strong case for these kinds of images that are very beautiful but with which the viewer has a strange relation in terms of the contrast between their aesthetic qualities and the information they contain. That is true, but beauty has an incredible political significance in the context of this conflict, and we tried to show it in these terms. When we talk about the panorama in terms of the picturesque and the pastoral, we claim that, in fact, beauty is thought of as both a commodity and a strategy in terms of the views from the settlements. It is there to draw the settlers in and ever closer to the Palestinian communities (which produce this beauty) â like a moth to a flame. It is a guiding principle that the settlements are urbanistically laid out in order to maximize the view. There is a paradox in this beauty in that what is considered by the settlers to be a pastoral, romantic panorama is actually the traces of the daily lives and cultivation of the Palestinians, and the settlers both enjoy that view but simultaneously supervise it. The settlers obviously have a very ambiguous relationship to this. On the one hand, the view creates for them a kind of biblical landscape that they admire, a way of life that seems to them more authentic. Yet they are, in fact, there to destroy and replace it. It was also interesting to see the physical relationships of the settlements and the Palestinian towns â how close they sometimes are to each other and how different the building forms were, although, in the more close-up photos you could see some similarities, too. When you look at a Palestinian village near a settlement, many times you'll see that the houses that are very near to the fence â nearest to the settlement â imitate the red roofs of the settlement, usually with red painted asbestos placed on their flat roofs. So, for example, the architectural sign of a red roof, which for the Israelis is basically a rural, suburban idea of the home, is for the Palestinians a sign of progress, modernity, and luxury â everything they strive for and want to emulate. It is very strange. When you drive through the West Bank, you see the great influence of settlement architecture on Palestinian architecture, and vice versa. In a sense there is a kind of disturbing mutual admiration stretched along the double-poled axis of vision. The settlers try to learn from the Palestinians how to live in nature; they see the Palestinians as the authentic component there, something that they would like to be but cannot. But in Israeli architecture, that trope of the red, sloped roof is itself a really displaced kind of beauty â a borrowed European, almost Tyrolean, form that in its right context has a purpose but here is not at all suited functionally to the environment. It functions in the settlements as a sign. Many times, settlement building codes require that anyone building their own home must build with this red roof because it's a sign that differentiates the "us" from the "them." And I have heard of a residents' meeting where settlers tried to resist the red roof â saying it's a misplaced European element, etc. â while people from Gush Emunim, the main settler body, forced them to build them if only to show Jewish presence. Before the Intifada, when you could still go into the West Bank to Palestinian hummus restaurants, they would quite often have wallpaper of, say, a Swiss landscape on the whole wall. Out the window you could see an equally, or even more, beautiful landscape, but the "ideal" was somewhere else â in Switzerland, somewhere in the West â not where they were. In addition to the photographs, the catalogue has an aggregate map you've put together of all the different settlements. Is that information itself contested by the Israeli government? Or was the compilation the difficult part of the process? This map is a joint project between myself and the human rights organization B'Tselem that was done in the context of a human rights report on violations through architecture and planning. Nobody contests its accuracy, and some in the Israeli establishment even work with it. I've recently heard that even some settlers' organizations use it. Last summer we presented it to the American administration, to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, to the State Department, and the Pentagon. They checked it and verified it and are now working with it. That is a great achievement for us. Conducting policy with this map is something we think is going to inevitably change the discussion. Whose maps were used before? Did the Palestinians present their own maps of the settlements at the peace negotiations? Were there two competing versions of reality offered? The best source for mapping the West Bank was always the CIA. A few times a year they took satellite photographs of the West Bank and produced a kind of status report on the built fabric of the settlements. These were usually classified for a period of time and then released. The novelty in our map is that we actually took and were able to trace almost all the master plans for future settlement growth. These supposedly have to be published, but obviously the government and the regional councils do not have any interest in the Palestinians knowing the master plans. The government is bound by law to make the documents public, so they post them within the settlements, which the Palestinians obviously cannot enter. When we sent letters asking to review the master plans, the councils threw a lot of obstacles in our way and we finally had to threaten them with a petition to the HCJ. Then they gave us some maps, but always old maps, and then they'd say, "Oh, sorry." What is the government worried about in terms of what the maps revealed? Well, the expansion of settlements is guarded almost like a military secret. So it was less a question of the identification of the settlements as they are than the projections of what the settlements will turn into? Exactly. This is a map of a possible future of the settlements and of the West Bank. What general conclusions did you draw from the map when you actually saw it, either ideologically or in terms of planning issues? Most other maps of the West Bank show the settlements as points. They show the location, perhaps the number of settlers in them. But by actually showing form, we were trying to make a connection between the very organization of matter across the landscape and human rights violations. So it's not only the fact that settlements are there, but it is the forms of the settlementsâtheir shape, and sizeâthat are contrary to human rights. For example, if you look at Ariel, which is an urban settlement located west of Nablus, it has an elongated banana shape. This is something you don't see in a map where it's depicted as a point. And you ask yourself, "Why was the settlement built like that?" If a student of ours came up with a plan of a city like that, we would say, "You must be joking! It maximizes traffic, does not allow pedestrians to walk, does not serve the population." So there must be other considerations involved. You start breaking down the formative forces that operate on the form of this stain on the map. On the one hand, the settlement wanted to stretch itself as long as possible along Route 505, which is one of the most strategic east-west arteries, an artery that Israel believes would have an armed column going down it in the event of a Jordanian or Iraqi invasion from the East. So the settlement spreads thin as long as possible along that road. On the other hand, it creates a complete wedge across the north-south axis and separates Salfit, which is a regional Palestinian center, from the villages to its north that rely on it for their economy. Another thing that it does is envelop Salfit and prevent it from growing in the direction it would like to. All these are done by formal manipulations, decisions taken by architects and plannersâsomething that shows that we have here a policy of negative planning. In architecture lingo, we call this weak form. Weak form reacts to a kind of force field that operates around it. Imagine a drop of water that is running on a particular surface and it reacts to the surfaceâin this case, to topography, but also to the temperature of the surface, its slope, air flow, etc. There are many political and strategic forces that stretch the forms of the settlements one way or another. The very forms embody the momentary balance of forces that created it. What Rafi Segal and I did at our office was to try and read backwards from the form of the stain on the map in order to recreate and understand the forces that manipulated it. With this method of observation, you can see the objectives of the planner. This is our point: It is not only that the settlements are there. If that were the only case, you could argue that it is not the responsibility of the architect and only of the political decision that placed it. But when the form is designed in a particular way to achieve strategic and national goalsâbisect a Palestinian road, surround a Palestinian settlement, or to try to create a wedgeâthe architect is engaged in negative planning, a reversal of his professional practiceâlike a medical doctor involved in torture. This approach establishes architecture, just like the tank, the gun and the bulldozer, as a weapon with which human rights could be and are violated. The mundane elements of planning and architecture are placed there in order to disturb and dominate, and when an architect is designing in order to disturb the growth of other things, he's not acting as an architect. You would say it is unethical. This is completely unethical! And it's not architecture. If there are violations of human rights in the plans the architect is proposingâin the way he is designing the houses, in the orientation of the windows, in every detail on both the architectural and the urban scaleâthen these actions are unethical and illegal. This incriminates the architectural profession. If the architect were just ignoring the Palestinians, it would look completely different. This is much worse. This is why there was a huge controversy here with the publication of A Civilian Occupation. Basically, the architects were like Leitersdorfâliberal, educated, most often Labor supporters who see themselves as building in the West Bank in a way that best serves the Jewish population there. But that is obviously not true. And we were trying to break out the reasons for why the forms are the way they are and reflect from that backwards on the whole ethics of architecture in Israel. So when someone like Leitersdorf says, "I was given no criteria, but I came back with three sites that took into account air pollution, traffic, commuter routes," and so onâis it your opinion that all of those criteria hide some other criteria that he's not willing to confront? Obviously. If you look at the 1984 government guidebook, it only speaks of the view. But what is this view? Is it simply the pastoral, Biblical landscape that you want to provide every citizen? No, because when you read the larger scale master plans outlining regional strategy, you see how they value observational points, and that their plans lay out a net of visual control vis-à-vis the Palestinians, the roads, and the strategic arteries. The overall master plans of the army and the settlement body are at least more honest in their aims than the architects. The architects themselves are not willing to admit to it, so they internalize those regional principles but argue for them in a completely different way. The wall-and-tower architectural model of the kibbutz that you discuss in the catalogue seems to be a precedent for the kind of visual mastery that the settlements strive for. The kibbutz in the plain was also an attempt to politicize the landscape and make it all into one homogenous field over which visual control could be exercised and over which territorial claims could be made. What is the relationship between that kind of architecture and what we see in the West Bank today? When we edited the catalogue we thought of it as an evolution. The wall-and-tower is argued by Sharon Rotbard to be the seed of Israeli architectureâprotective and observant at the same time. The reason it was built in that way was because they were building on a plainâyou didnât have the protection of the heights and you needed the wall, and the eye was centralized within the tower. Now the settlements are doing the same thing, creating both the wall and the eye within the very distribution of matter across the landscape. The mountain is both wall and tower. Yes. Planning and architecture has always been the executive arm of the Zionist state; the state has always used it in a very political way to set borders, to take land and to make the development and sustainability of Palestinian areas as difficult as possible. Apart from the controversy, what has the reception of catalogue been like outside of Israel? Has it been seen as relevant to other situations in other places? Itâs incredibly relevant. Most of the contributors to the catalogue describe Israel as a kind of laboratory where elements of both modernity and tradition are played out in a very powerful way against each other in a very intense environment. If you think about the mountain and the creation of a suburban settlement, youâll see itâs around the same time that Americans are inventing the gated community. Itâs essentially a local form of the gated community. What you see in the West Bank is basically the same phenomenon you see in Los Angelesâs Orange County, Brasilia, Mexico City, and other places but in a much more violent and extreme way. Itâs the end condition of those urban pathologiesâit shows the worst-case scenario of where those kinds of urban arrangements could be going. And I think the questions we are trying to pose in the catalogue about the responsibility of the architect are applicable everywhere. You have written that the geometry of the occupation can only be understood in three dimensions. There are questions of the underground sewage, archaeology, tunnels, the water reservoirs, the air space above, and so on. These are issues that came up in the peace talks, of course. But the map you have produced is two-dimensional. What would it mean to map this conflict three-dimensionally? Itâs interesting to look at how, for example, an Israeli highway passes over a Palestinian road or look at how the tunnels intersect. I am currently working on a computer-based interactive three-dimensional map of the West Bank with my colleague, Reed Kram. The over-complication of the surface as shown on our mapâthe fact that itâs no longer possible to draw a continuous line that separates Palestinians from Israelisâmade clear to the negotiating parties during the peace process that a two-dimensional solution is no longer possible. Shimon Peresâs Oslo proposal was to give the Palestinians limited sovereignty on the land but to retain Israeli sovereignty of the subsoil and the air over it. So you have a kind of sandwichâIsrael, Palestine, Israelâacross the vertical dimension. Peace techniciansâthe people who are always drawing new maps for a solutionâarrive at completely insane proposals for solving the problem of international boundaries in three dimensions. And when you have Jewish enclaves in Palestinian territory, you have to build either tunnels or bridges that connect them to each other. Both typologies were experimented with and proposed throughout negotiations. The most obvious is the proposed safe passage between the West Bank and Gaza that has a Palestinian road with Palestinian sovereignty that goes over Israelâs sovereign territoryâwith the international boundary being the thermodynamic joint between the column and the road. We get into incredibly bizarre and dystopian solutions. Jerusalem itself, according to the Clinton plan, would have had 64 kilometers of walls and 40 bridges and tunnels connecting the enclaves to each other. Imagine an urban environment that operates like that. It would make L.A.âs highway system look flat. This is the total collapse of the idea of territory as produced by maps. Nationalism and mapmaking were always bound together. You had a map and you drew a boundary. But what you see in the West Bank is that sovereign relations are attempting to play themselves out three-dimensionally. And that is obviously an unworkable absurdity. We do not think that there is a viable "design solution" to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The perfect line that brilliantly weaves itself through the terrain and answers in its path both national demands, the one line that everybody from Ben Gurion to Barak was looking for, simply does not exist. Nor does it exist in these three-dimensional boundary contortions. These just accentuate the exhaustion and the frustration of all possible lines on the two-dimensional plane. This territorial conflict is such that it must be addressed in a non-territorial and thus non-formal way. If you think of similar conflicts between a settling nation and a native nation, there is no historical precedent for the idea of partition. We think that the way to manage this conflict is not through the creation of another sovereign state but within the realm of law. Instead of thinking of two states side by side, something that our research shows is impossible without integration on the planning and infrastructure level, we would like to propose the idea of a simultaneous overlap: two states that are not lying side by side but overlap legally across the same territory. This obviously entails a new definition of national sovereignty, one in which a choice of more than one citizenship is available for the same area.