Innovative Minds © 2014. All Rights Reserved. www.inminds.co.uk | |||||

|

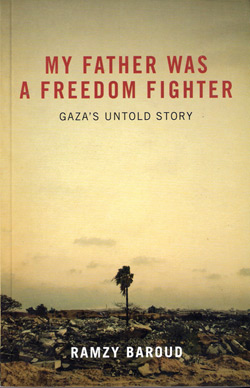

[Other] Ramzy Baroud: My Father Was A Freedom Fighter - Gaza's Untold Storyinminds On 25th March 2011, Palestinian activist Maha Rahwanji hosted a mesmerising evening in conversation with Ramzy Baroud, the editor-in-chief of the Palestine Chronicle, about his recent book 'My Father Was A Freedom Fighter - Gaza's Untold Story'. The book can be described as a 'peoples history' of Palestine - by following the lives of one family - the authors, the heart-rending history of the Palestinian people from the ethnic cleansing of the Nakba, to growing up as refugees under Israeli occupation, and living and dying under siege in Gaza is laid bare in a very accessible form. The 85 minutes of riveting conversation was followed by 35 minutes of questions and answers. Full video of the event is provided below. The event was jointly organised by the Middle East Monitor (MEMO) and Palestine Solidarity Campaign (PSC). If you haven't checked it out yet, MEMO provides a refreshingly unique analysis of the Palestinian issue, insights which are hard to find elsewhere. Maha Rahwanji is an elected member of the executive committee of PSC.  Ramzy Baroud in conversation with Maha Rahwanji  My Father Was A Freedom Fighter Gaza's Untold Story by Ramzy Baroud In introducing Ramzy Baroud, Maha read a passage from his book describing a defining moment in Ramzy's life - Wednesday 9th December 1987 - when as a kid he joined the Intifada: "I picked up a stone, but stood still. Others ran away, but some ran towards the soldiers, with their rocks and flags. The soldiers drew nearer. They looked frightening and foreign. But when the kids ran in the direction of the soldiers and rocks began flying everywhere, I was no longer anxious. I belonged there. I ran in to the inferno with my school bag in one hand, and a stone in the other, "Allahu Akhbar!", I cried, and I threw my stone. I hit no target, for the rock fell just a short distance ahead of me, but I felt liberated; I was no longer a negligible refugee standing in a long line before an UNRWA feeding centre, waiting for a dry falafel sandwich. Engulfed by my own rebellious feelings, I picked up another stone, and a third. I moved forward, even as bullets flew, even as my friends began falling all around me. I could finally articulate, and for the first time on my own terms. My name was Ramzy, and I was the son of Mohammed, a freedom fighter from Nuseirat, who was driven out of his village of Beit Daras, and the grandson of a peasant who died with a broken heart and was buried beside the grave of my brother, a little boy who died because there was no medicine in the refugee camp's UN clinic. My mother was Zarefah, a refugee who couldn't spell her name, whose illiteracy was compensated for by a heart overflowing with love for her children and her people, a woman who had the patience of a prophet. I was a free boy; in fact, I was a free man."

Ramzy Baroud  Maha Rahwanji Ramzy whose family were ethnically cleansed from the village of Beit Daras, made an interesting observation of how the victors write history : "Unfortunately many people have never heard of the massacre of Beit Daras as well as the many massacres that took place in Palestine at the time simply because they were not validated by any other narrative aside from the Palestinian so they have kinda been discounted and dropped out of history, and its important we bring it back."

Ramzy Baroud There is a lot of discussion in liberal circles as to whether its a good idea for Palestinians to take up arms and resist the occupation. Ramzy, using the example of his father, makes nonsense of such conjecture: "My father was 10, and there was really nothing in Gaza as far as survival is concerned except on relying on the trickles of aid that was coming and also on begging. So he began to beg along with 1000s of other children in Gaza. But what do you do when everyone is poor, where do you do begging? One of the places he went was the Egyptian army encampment, now the Egyptian army was defeated and they were still in Gaza at the time. He would go and extend his arm through the fence, and along with so many children hanging around for so long hoping for a piece of bread, and that's what he did. You can imagine the level of humiliation that he felt as a child going through this. I think there, that was the moment where the whole concept of freedom fighting [came], I think it was directly related to the loss of Palestine and the level of collective humiliation that was felt by the Palestinian refugees. We think violence and non-violence, resistance and no-resistance, we always subscribe to this kind of discourse that this is almost like a technical question or a tactical question, you know should Palestinians use violence or not. I think if you truly appreciate Palestinian history, again the way it is , not the way we think it ought to be, you would truly understand that resistance in Palestine was not a matter of strategy, it was a matter of necessity. And that's how the fedayeen, the freedom fighters, concept became part and parcel of the collective Gaza psyche."

Ramzy Baroud In giving his reasons for writing the book, Ramzy explained how the telling of Palestinian history is often distorted in two ways and as a result the real Palestinian narrative is lost: "It wasn't necessarily about me, exposing my family or trying to tell stories. Its because I felt that the Palestinian narrative has been neglected, or it has been discoloured or tainted somehow. There is something that I call 'history by association' - its when we try to tell our history, because we know it will not be accepted the way it is for many reasons including racism and the dehumanisation of the Palestinian people, so what we do is - two kinds of History actually. 'History of negation' which is trying to prove through our history that we are not what you think of us. So I'm going to tell you why Palestinians are not terrorists - trying to always respond to an already created discourse about who we are - so thats the history of negation. And the 'history of association' is where in order for me to explain to you, to make my cause more relevant, amiable I have to constantly borrow from other historical experiences, which is important I think - apartheid South Africa or American imperialism in South America, and so forth and so on. But at the end of the day our history ended up being a kind of concoction of so many versions of history. The authentic history of Palestine, and the authentic narrative is not centralised in all of this, its always on the margins. And I thought its really time to change this.."

He also explained that when Palestine hits the news the story is presented disconnected from its historic background and hence robs it of its humanity: "And I try to do some justice to Gaza because when Gaza is discussed in the media and wrote about, again its presented as a crisis - people are dying.. people are starving.. there is very little by way of historical connections why people are dying. And when we do, referring to history we are very short sighted, how we sight history.. the 8 Palestinians who were killed in Gaza recently they included 3 children. We know very little about those children - where do they come from? Where do their parents come from? Why are they in Gaza in the first place? There is always that disconnect. And then we talk about 8 and someone else will say 'but Palestinians fired rockets first' and we say 'no, no, no if you refer to the BBC report on such and such a date it was Israel that..' and we enter in this kind of useless argument and counter argument by presenting a history that is devoid of humanity, devoid of people, devoid of the fact that no it wasn't about the number of people who were killed but about why they were killed why they were there, that's why I think its so essential we bring back the Palestinian [narrative].."

He also compared this with the "the preception of the Israel narrative" which is centred in an "Israeli-centric history" always going back to the holocaust.  Ramzy Baroud Ramzy Baroud had some advice for supporters of Palestine, especially those in Europe: "This is the time where civil society becomes effective. We have the critical mass in European societies, the question is how to we channel that support to achieve political ends. I think not only do we need to redefine the Palestinian narrative within the discourse, I think we need to redefine our relationship to the discourse as a whole. What I mean by that is that I don't think we should be consumed too much with one-state two-state / violence non-violence - that is an issue that Palestinians will sort out on their own, because they have their own dynamics, and these dynamics are happening independently of whatever the activists in Norway decide or don't!

I was in South Africa recently and I spoke to a group of lovely people in Johannesburg, but then I was told Ramzy you are telling us all of this yet the Palestinians are not united which makes it difficult for us.. but then I discovered when I was there that there were still some military contracts that were signed by the apartheid government of South Africa and Israel that were never really cancelled. And those military contracts included explosive bullets that are being shipped to Israel.. then I asked that gentleman did you know all of this, he said no. There I am thinking that my gosh here is this brother in Johannesburg so worried about Hamas and Fatah reconciling or not and he doesn't realise that he's actually funding, as a tax payer, he is paying for all of this. So I'm thinking we have got to reposition ourselves as well. The battle for us is not Jerusalem, its not Ramallah, its not Gaza. These are important, it should inspire our battle, but our battle is London, and Leeds, and Toronto and Johannesburg. We are not going to liberate Palestine, the Palestinians will. But we want to morally divest from Israel, and I think that this is even more important than the practical divestment. The moral divestment - I want to have nothing to do with you, what ever happens, happens in this conflict but I'm not going to fund your war machinery, I'm not going to contribute to your vile acts in Palestine.." Ramzy Baroud followed this up in the question answer session when responding to a local activist: "I think there are two narratives. One is how does this conflict relate to you as someone who is living in London, and then as someone who is living in the UK, and then as someone who is living in Europe. So you need to localise. We as Palestinians we need to internationalise our narrative and we want to reach a point where I don't have to borrow from anybody's history. And I would say Nakbha and you would understand exactly what that's all about, I'd say Naksa and you would immediately understand. So we need to internationalise a conflict that has been localised by Oslo and the Palestinian Authority and divided us politically, and socially, and then territorially in to areas A, B and C and with all these divisions we also became divided from within, psychologically we became divided - we need to change all that. But you cannot become international, you have to localise it because matters to you because that grocery store across the street is selling Israeli products.."

Ramzy Baroud What the question and answer session revealed was the rare participation of so many passionate Palestinians. They made a welcome change. One of the gems that one Palestinian in the audience contributed, which resulted in the whole hall laughing in agreement, was when referring to Mahmoud Abbas: "Why do we accept, why do you say president, president of what? He's not even president of his shoes!"

He followed this with a serious point of asking the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign and other pro-Palestinian organisations to "get out of this shame" of recognising Mahmoud Abbas's PA as a representative of the Palestinian people. Ramzy also made a poignant point about talk of unity between principled Hamas and collaborationist Fatah: "If Hamas and Fatah decided to unify.. around the lines that are not accepted by the Palestinian people, is that okay? Of course not. So its not really the unity per say, its around what platform are they uniting and is this platform consistent with the rights of the Palestinian people.."

Ramzy Baroud Ramzy Baroud's book ends with his father Mohammed's vote for Hamas, because the are "decent people", being punished by the international community and Israel with an even tighter siege of Gaza: Gaza's, and Mohammed's isolation was complete: Mohammed's sons could no longer send him money, as the boycott extended to reach all financial institutions as well. Desperate, he sold his house, the last tangible connection he had to his beloved Zarefah. That beautiful and battered place that had stood the test of time and bullets was sold for scarce medicine, smuggled through Gaza's tunnels, on which Mohammed depended to breathe..

"Son, I am dying," he softly mumbled on the phone. "I am sorry, Dad. I am so sorry. I wish I could be there with you. I wish I could do something. I wish it was me, and not you, Dad." "Son, I love you. May Allah bless you and your children.".. Thousands of people descended to his funeral from throughout Gaza; oppressed people, who shared his plight, hopes and struggles, accompanied him to the graveyard where he was laid to rest. He didn't even have the money to buy his own coffin. I have often thought it to be a great mercy that Palestinians must only endure Israel's occupation for one lifetime. The resilient fighter had finished the battle for a well-deserved moment of peace. To read the articles Ramzy Baroud has written and to learn about the many books he has authored please visit http://ramzybaroud.net.

Video: Ramzy Baroud: My Father Was A Freedom Fighter - Gaza's Untold Story

Source: inminds.com Related ArticlesAlso Of InterestPage URL: http://inminds.com/article.php?id=10510

|

|

Support Us

If you agree with our work then please support us.Campaigns INMINDS Facebook Live Feed Latest Video's

INMINDS Twitter Feed Tweets by @InmindsComFeatured Video's

You need Flash player 8+ and JavaScript enabled to view this video.

[all videos (over 200)..] Featured MP3 Podcast  "For most journalists, whether they realize it or not, are groomed to be tribunes of an ideology that regards itself as non-ideological, that presents itself as the natural center, the very fulcrum of modern life. This may very well be the most powerful and dangerous ideology we have ever known because it is open-ended. This is liberalism." Campaigning Journalist and Film-maker Socialism 2007 Conference, Chicago [43min / 21Mb] [all podcasts..] Newsletter Feedback |

|

|